I have bought several novels published by Persephone Books for myself or as presents either by ordering online or visiting their exquisite shop in Conduit Street in London. They make marvellous presents for reader- and writer-friends.

This

publisher - dedicated to reprinting neglected fiction and non-fiction mid

twentieth century books, mostly by women - must be unique on the contemporary

publishing scene in that they show high respect writers and readers and have a

brilliant sense of the aesthetic and physical nature of books.

This

was brought home to me when I came across a copy of their 2014 winter

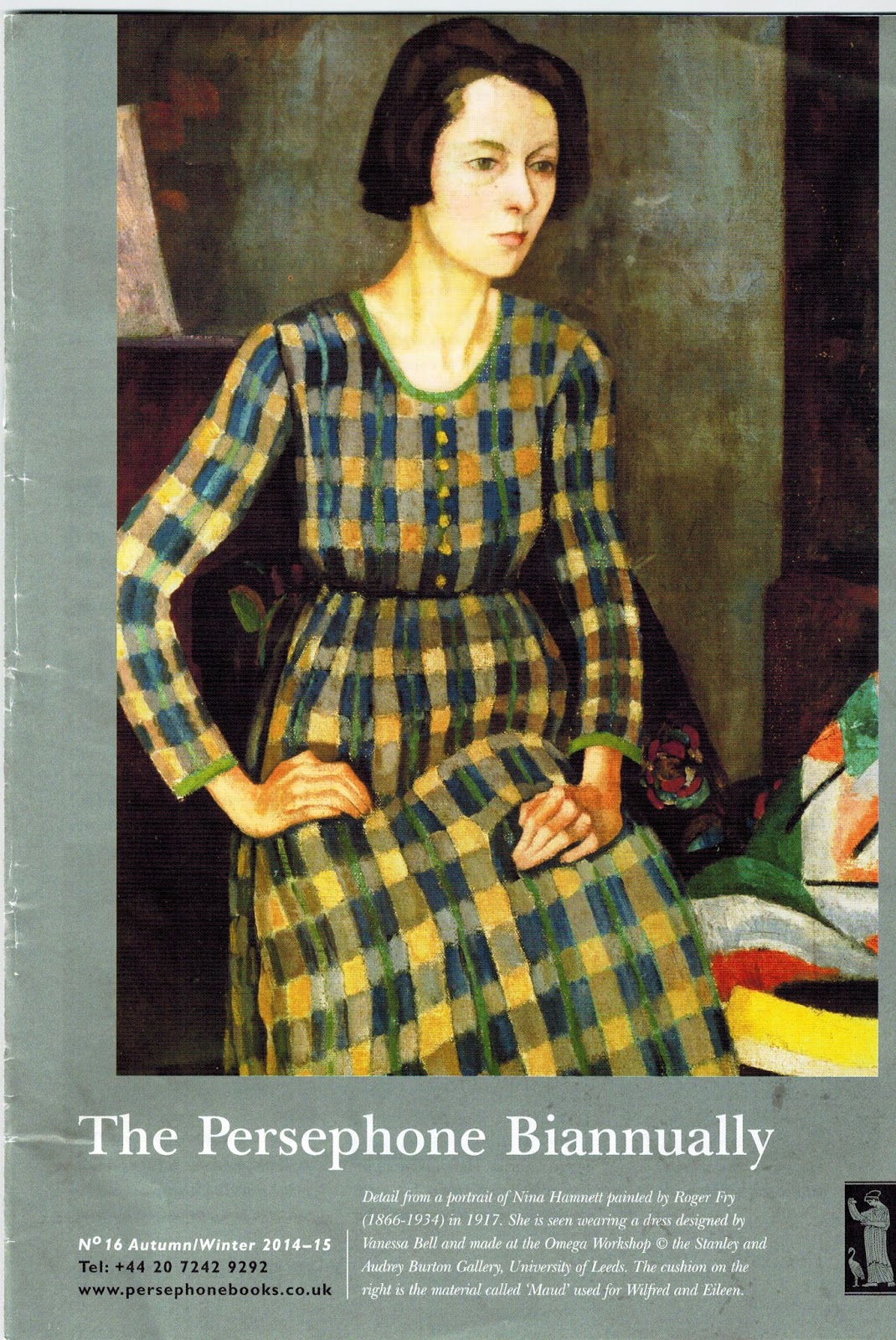

catalogue called The

Persephone Biannually, It is

truly a beautiful object featuring paintings and images from the 20th Century

art and essays by contemporary writers which serve as forwards and afterwards

of the re-published novels.

I was particularly delighted to read Harriet Evans's* passionate and iconoclastic essay introducing Dorothy Whipple's novel 'Because of The Lockwoods.' It is worth getting hold of Persephone Biannually just for this essay alone. Like me you will be movedo to buy Dorothy Whipple's Persephone novel.

In her essay of appreciation Harriet Evans says

'... the world of Literary London, for want of a better expression, is today

perhaps more sexist and snobbish (especially geographically snobbish), almost

unbelievably, than it was when she was writing, than in the time when she was

writing and the cultural tide of opinion and the cultural tide of of opinion,

is these days against her. Another reason why Whipple has been disregarded by

the literary mainstream is that we still live in a sexist world and in addition

one where writing from the North of England is undervalued.'

'... the world of Literary London, for want of a better expression, is today

perhaps more sexist and snobbish (especially geographically snobbish), almost

unbelievably, than it was when she was writing, than in the time when she was

writing and the cultural tide of opinion and the cultural tide of of opinion,

is these days against her. Another reason why Whipple has been disregarded by

the literary mainstream is that we still live in a sexist world and in addition

one where writing from the North of England is undervalued.'Looking back on a lifetime of writing from the North of England I can heartily endorse this.

*Harriet

Evans, now a very successful novelist, was once my own very much appreciated

editor. W.

Dorothy Whipple and her books. Click here

http://www.persephonebooks.co.uk/dorothy-whipple/

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)